12 Akbal

Blue Crystal Night

Ask me to stem the great Ocean’s Tide

Ask me to halt the Moon’s silver Ride

Ask me to bless the Blind with clear Sight

Ask me to banish all Darkness from Night

Ask me to heal the Wounds of the World

Ask me to find the Oyster’s sweet Pearl

Ask me to live without Water or Air

Ask me to cut off my Breath or my Hair

But ask me not ever to cease loving you

For that is the one Thing I never could do.

©Kleomichele Leeds

Elizabeth Jennings Graham

Elizabeth Jennings Graham (March 1827 – June 5, 1901) was an African-American teacher and civil rights figure.

In 1854, Graham insisted on her right to ride on an available New York City streetcar at a time when all such companies were private and most operated segregated cars. Her case was decided in her favor in 1855, and it led to the eventual desegregation of all New York City transit systems by 1865.

Graham later started the city's first kindergarten for African-American children, operating it from her home on 247 West 41st Street until her death in 1901. In 2007, New York City co-named a block of Park Row "Elizabeth Jennings Place" after a campaign by children from P. S. 361.

Early life

Elizabeth Jennings was born free in March 1827. Her parents, Thomas L. Jennings (1792-1859) and his wife, also named Elizabeth (1798-1873) had at least five children. He was a free black and she was born into slavery. He became a successful tailor and an influential member of New York's black community as the first known African African-American holder of a patent in the United States. In 1821, he was awarded a patent from the U.S. government for developing a new method to dry-clean clothing. With fees from his patented dry-cleaning process, Thomas Jennings bought his wife's freedom, as she was considered an indentured servant until 1827 under the state's gradual abolition law of 1799. Their daughter Elizabeth, then, was born free and received an education.

Elizabeth Jennings's mother was a prominent woman known for penning the speech "On the Improvement of the Mind," which ten-year-old Elizabeth delivered at a meeting of the Ladies Literary Society of New York, which was founded in 1834 and of which Elizabeth's mother was a member. The literary society was founded by New York's elite black women to promote self-improvement through community activities, reading and discussion. Written and delivered in 1837, the address discusses how the neglect of cultivating the mind would keep blacks inferior to whites and would have whites/enemies believe that blacks do not have any minds at all. Jennings believed the mind was very powerful and could help to abolish slavery and discrimination. Therefore, she called upon black women to have a mind and take action. The importance of improving the mind was a consistent theme among elite black women.

By 1854, Elizabeth Jennings had become a schoolteacher and church organist. She taught at the city's private African Free School, which had several locations by this time.

Jennings v. Third Ave. Railroad

In the 1850s, the horse-drawn streetcar on rails became a more common mode of transportation, competing with the horse-drawn omnibus in the city (Elevated heavy rail, the next transportation mode in the city, did not go into service until 1869). Like the omnibus lines, the streetcar lines were owned by private companies, and their owners and drivers could refuse service to any passengers. They enforced segregated seating.

On Sunday, July 16, 1854, Jennings went to the First Colored Congregational Church. As she was running late, she boarded a streetcar of the Third Avenue Railroad Company at the corner of Pearl Street and Chatham Street. The conductor ordered her to get off. When she refused, the conductor tried to remove her by force. Eventually, with the aid of a police officer, Jennings was ejected from the streetcar.

Horace Greeley's New York Tribune commented on the incident in February 1855:

She got upon one of the company's cars last summer, on the Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor undertook to get her off, first alleging the car was full; when that was shown to be false, he pretended the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but (when) she insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her. She resisted. The conductor got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, soiled her dress and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered, but she effectually resisted. Finally, after the car had gone on further, with the aid of a policeman they succeeded in removing her.

The incident sparked an organized movement among black New Yorkers to end racial discrimination on streetcars, led by notables such as Jennings' father Thomas L. Jennings, Rev. James W.C. Pennington, and Rev. Henry Highland Garnet. Her story was publicized by Frederick Douglass in his newspaper, and it received national attention. Jennings's father filed a lawsuit (on behalf of his daughter) against the driver, the conductor, and the Third Avenue Railroad Company in Brooklyn, where the Third Avenue company was headquartered. This was one of four streetcar companies franchised in the city and had been in operation for about one year. She was represented by the law firm of Culver, Parker, and Arthur. Her case was handled by the firm's 24-year-old junior partner Chester A. Arthur, future president of the United States.

In 1855, the court ruled in her favor. In his charge to the jury, Brooklyn Circuit Court Judge William Rockwell declared:

Colored persons if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by any rules of the company nor by force or violence.

The jury awarded Jennings damages in the amount of $250 (comparable to $6,000 to $10,000 in 2015 dollars) as well as $22.50 in costs. The next day, the Third Avenue Railroad Company ordered its cars desegregated.

As important as the Jennings case was, it did not mean that all streetcar lines would desegregate. Leading African-American activists formed the New York Legal Rights Association to continue the fight. In May 1855, James W. C. Pennington brought suit after being forcefully removed from a car of the Eighth Avenue Railroad, another of the first four companies. After steps forward and back, a decade later in 1865, New York's public transit services were fully desegregated. The last case was a challenge by a black woman named Ellen Anderson, a widow of a fallen United States Colored Troops soldier, a fact that won public support for her.

Later life

Elizabeth Graham married Charles Graham (1830-1867) of Long Branch, New Jersey on June 18, 1860, in Manhattan. They had a son, Thomas J. Graham. He was a sickly child who died of convulsions at the age of one during the New York Draft Riots of July 16, 1863. With the assistance of a white undertaker, the Grahams slipped through mob-filled streets and buried their child in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn. The funeral service was read by Reverend Morgan Dix of the Trinity Church on Wall Street.

After the New York Draft Riots of July 1863, there were numerous attacks against the African-American community. Jennings and her husband Charles Graham left Manhattan with her mother to live with her sister Matilda in Monmouth County, New Jersey, in or near the town of Eatontown, New Jersey. Her husband Charles died in 1867 while they were living in New Jersey. Four years later, Jennings, along with her mother Elizabeth and sister Matilda, moved back to New York City in the late 1860s or 1870.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham lived her later years at 247 West 41st Street. She founded and operated the city's first kindergarten for black children in her home. She died on June 5, 1901, at the age of 74, according to her tombstone, and was buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery along with her son and her husband.

Legacy

Streetcar to Justice

On January 2, 2018, the first biography of Elizabeth Jennings was published, written by Amy Hill Hearth. Entitled Streetcar to Justice: How Elizabeth Jennings Won the Right to Ride in New York, and intended for middle-grade to adult readers, the book was published by HarperCollins/Greenwillow Books in New York.*

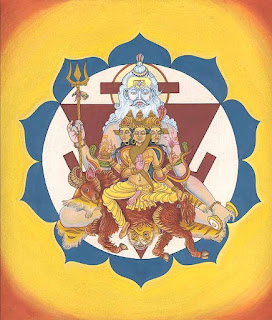

AKBAL

Kin 103: Blue Crystal Night

I dedicate in order to dream

Universalizing intuition

I seal the input of abundance

With the crystal tone of cooperation

I am guided by the power of vision.

As we are imprinted with the new galactic program, we open to a whole nexus of psychic compression within a mythic frame of reality.*

*Star Traveler's 13 Moon Almanac of Synchronicity, Galactic Research Institute, Law of Time Press, Ashland, Oregon, 2018-2019.

The Sacred Tzolk'in

Manipura Chakra (Limi Plasma)

No comments:

Post a Comment