Pitseolak Ashoona, “Woman Hiding From Spirit” (1968)

stonecut, 27 1/4 x 24 1/4” (courtesy Dorset Fine Arts)

A Family of Artists Creates a Portrait of Inuk Life Across Three Generations

The exhibition of work by Inuk grandmother, mother, and daughter contains prints and drawings that resonate with intergenerational themes of motherhood and community.

Three generations of artists from Kinngait, the renowned center of Inuit printmaking best known as Cape Dorset, are on view in an exhibition that consists of a century-spanning matrilineal exchange of forms, stories, and values. Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait is titled for the Inuktitut word akunnittinni, meaning “between us,” and features work by Inuk grandmother, mother, and daughter Pitseolak Ashoona, Napachie Pootoogook, and Annie Pootoogook. Their prints and drawings resonate with intergenerational themes of motherhood and community, and the exhibition is itself a sampling of the history of the resilience of Inuit life in the face of the complexities of modernity and globalization as seen through the lens of a single, extraordinary family of artists.

Work from Kinngait is not infrequently shown in New York. Most recently, in late 2016, the Brooklyn Museum presented programs with the Cape Dorset Legacy Project to supplement its collection of Kinngait work from the 1950s to the present. It is also a major moment for Inuit artists internationally. Kananginak Pootoogook, a family member and one of the first Kinngait printmakers, is now the first Inuit artist to be shown at the Venice Biennale, having been selected for this year’s Arsenale exhibit seven years after his death. Closer to home, the exhibition SakKijâjuk, organized by Heather Igloliorte — the first major show of Labrador Inuit art — is now currently touring across Canada.

Pitseolak Ashoona, “Dream Of Motherhood” (1969)

stonecut, 33 3/4 x 24” (courtesy Dorset Fine Arts)

However Inuit art’s popularity has never taken off in the United States in the way it has in Canada. In part, this is due to the history of Inuit print making’s ties to efforts by the Canadian federal government to promote Inuit arts as a means of economic sustenance for northern communities and the resultant craze for the highly collectible work that emerged in the rest of the country. In 1957, James Houston, a representative of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, later hired by the Department of Northern Affairs, introduced techniques of printing to Kinngait with stone-cuts and stencils, and in 1959 he brought printing and workshop techniques from Japan to guide and organize the work of the newly incorporated West Baffin Eskimo Co-Operative. Under these Japanese methods, original drawings by artists were chosen by separate block-cutters and printers who completed the printing process, and for the first two decades of its operations a team of nine men did the majority of the block cutting and printing at Kinngait. The co-op model encouraged profit sharing and consensus decision making, and the egalitarian setting allowed Inuit values to operate with support from business savvy of advisors like Houston who capitalized on the market’s desire for what it saw as authentic representations of Inuit culture.

At the same time, this model accommodated southern Canadian desires and ambivalent feelings towards the Inuit, while modernizing Inuit labor and maintaining their traditional values and distinct culture as highly collectible works of art. While the first critics of Inuit art debated what precisely was “authentic” in Inuit art, southern audiences eagerly consumed work that often omitted elements of the contemporary in favor of timeless images of arctic life.

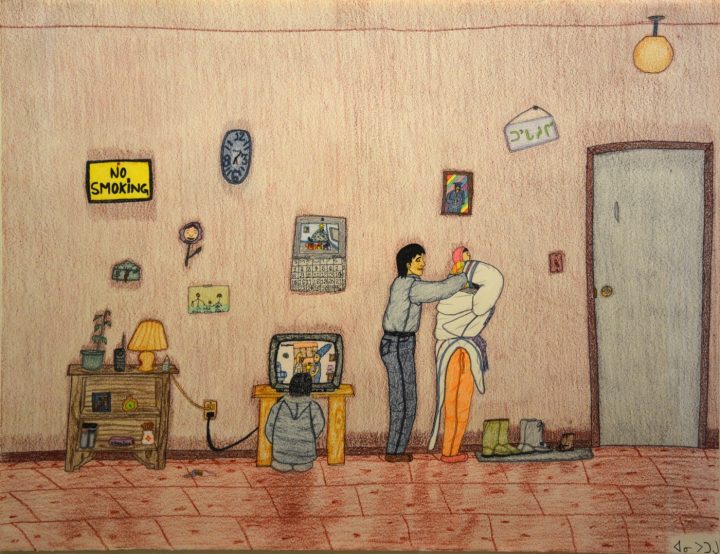

Annie Pootoogook, “A Portrait of Pitseolak” (2003–04)

colored pencil and ink on paper (courtesy Edward J. Guarino Collection)

The promotion of Inuit art was thus an attempt to encourage assimilation to a capitalist, colonial economic system and the formation of permanent settlements for indigenous peoples who had otherwise been self-sustaining while seasonally transient. Following its great popularity, Inuit art has since become a national symbol for Canada, as evidenced by the work of famed Kinngait artist Kenojuak Ashevak recently being added to the $10 bill. At the same time, it has flourished over the last sixty years as a site for individual Inuk agency and cultural expression that is resilient to and representative of the pressures that modernity has exerted on life in the North.

Akunnittinni, though, moves past the belabored topics of market making and the in/authentic modernity of Cape Dorset printmaking to pursue matrilineal discourses internal to the community. The effect is an inward-looking familial history, rather than one, as described above, that focuses on the needs and desires of southerners.

Pitseolak Ashoona’s drawings and designs were a feature of the beginnings of Kinngait print making, and her subject matter reflects the concerns of that early period. Born in 1904, she grew up with a family life of subsistence living, and, following the death of her husband, moved to Kinngait with several of her seventeen children to seek out an income. Her prints tend to omit signs of contemporary life and the south, as most early Kinngait work did, thus appealing to audiences seeking images of a timeless and pristine Arctic life. Ashoona often lingers on the spiritual as well as the stories and ways of life of previous generations. In “Woman Hiding from Spirit” (1968) the negative form of a female figure lays in front of a bear-like spirit that does not seem to see her. Sprouting from the spirit’s head are antlers and birds who fight over berries; the woman is nearly face to face with one such bird — speaking to the closeness of the human and spiritual worlds in the North. While none of Ashoona’s best known works are on display, prints like “Dreams of Motherhood” (1969) put the theme of the exhibition into the long line of generational knowledge that reaches back to precolonial life. Sitting on the main woman’s head is the image of a mother holding an ulu knife and carrying an infant in her hood — an image of transgenerational motherhood that is of a value beyond Euro-American consumption.

The tensions among such seemingly timeless subject matter, modern materials, and the production and marketing model of Dorset Fine Arts (the marketing division of the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative) vexed anthropologists seeking to define from an outsider’s perspective “authentic” Inuit culture. But as Napachie Pootoogook’s work shows, Kinngait prints have never shied away from chronicling the flux of life in the North. Her work on display shows some of the darker aspects of a history that certainly do not fit the idealized image of an innocent, unrecoverable Arctic life. In “Trading Women for Supplies” (1997-98) and “Whaler’s Exchange” (1989), women are given to Euro-American sailors in mercantile transactions of sexual exploitation exchanged for supplies. Cannibalism is the subject of “Eating His Mother’s Remains” (1999-2000), a practice that, while not part of Inuit culture except in case of extreme famine, has been projected onto many indigenous cultures throughout history. “Alcohol” (1994), depicting a group of figures reeling, with several bottles strewn about them, demonstrates Pootoogook’s foray into particularly contemporary issues that were not necessarily present in Ashoona’s work.

Napachie Pootoogook, “Alcohol” (1994) colored pencil and ink on paper

(courtesy Edward J. Guarino Collection)

It is the work of Annie Pootoogook that most strikingly demonstrates the ways traditional Inuit family life has been integrated into the modern North. This is the first substantial exhibition of Pootoogook’s work in New York since her widely mourned death in 2016 — a tragic reminder of the continued effects of the colonial legacy on indigenous women. Her drawings alone are reason enough to see the exhibition. A Sobey award winner in 2006 whose work was shown the following year in documenta 12 and in a 2009 solo exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian, New York, Pootoogook’s work brings her family’s legacy into the immediate present by exquisitely picturing the intimacies of family life in a North inundated with southern goods and media.

The bands of color in “Couple Sleeping” (2003-04) demonstrate how sensitively, with her colored pencils, she treats the same paper used for Kinngait prints, creating an alluring surface that recalls the starry texture of Ashoona’s early prints. It is the epitome of an Inuktitut word sometimes substituted for art, sanattiaqsimajut: “these things that are finely made.” “Watching the Simpsons on TV” (2003) is an intimate and lusciously detailed domestic interior scene of family life that fills the page with details of a contemporary Inuit experience. It is a stylistic break from the isolated Inuit figure as seen in the work of her mother and grandmother, yet she also draws on that heritage. “Pitseolak’s Glasses” (2006) depicts her grandmother’s eyeglasses in a near-abstract manner that is reminiscent of engraved ivory forms. And a portrait of Ashoona herself on an isolated white background, not wearing a point-hooded parka, but a patterned dress and headscarf, ties the three generations of the exhibition neatly together — akunnittinni.

Annie Pootoogook, “Watching the Simpsons on TV,” (2003)

pencil, ink, pencil crayon, 20″ x 26″ (courtesy Edward J. Guarino collection)

The selection of Annie’s work avoids some of the darker themes that she, like her mother, had taken up to critique the ongoing legacy of colonialism in the North. But the repeated emphasis on family and generational conversation rooted in matrilineal love and care can do the same work. The thematic connections across the generations of this family — motherhood, Inuit life in the face of modernity, and resilience — tell their own history of the Inuit response to an increasingly globalist present. Counter to the ambivalence that defined the southern reception of modern Inuit printmaking, Akunnittinni presents a model of intergenerational relations rooted in the Kinngait community that stands in the face of an increasingly globalist and precarious present.

Akunnittinni: A Kinngait Family Portrait continues at the National Museum of the American Indian, New York (the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House

One Bowling Green, the Financial District) through January 8, 2018.*

By Christopher Green

IX

Kin 114: White Planetary Wizard

I perfect in order to enchant

Producing receptivity

I seal the output of timelessness

With the planetary tone of manifestation

I am guided by the power of spirit

I am a galactic activation portal

Enter me.

Samadhi is the state of entering prolonged union with the all-abiding reality where there is no thought.*

*Star Traveler's 13 Moon Almanac of Synchronicity, Galactic Research Institute, Law of Time Press, Ashland, Oregon, 2017-2018.

The Sacred Tzolk'in

Muladhara Chakra (Seli Plasma)

No comments:

Post a Comment